We're Eighty Years Early

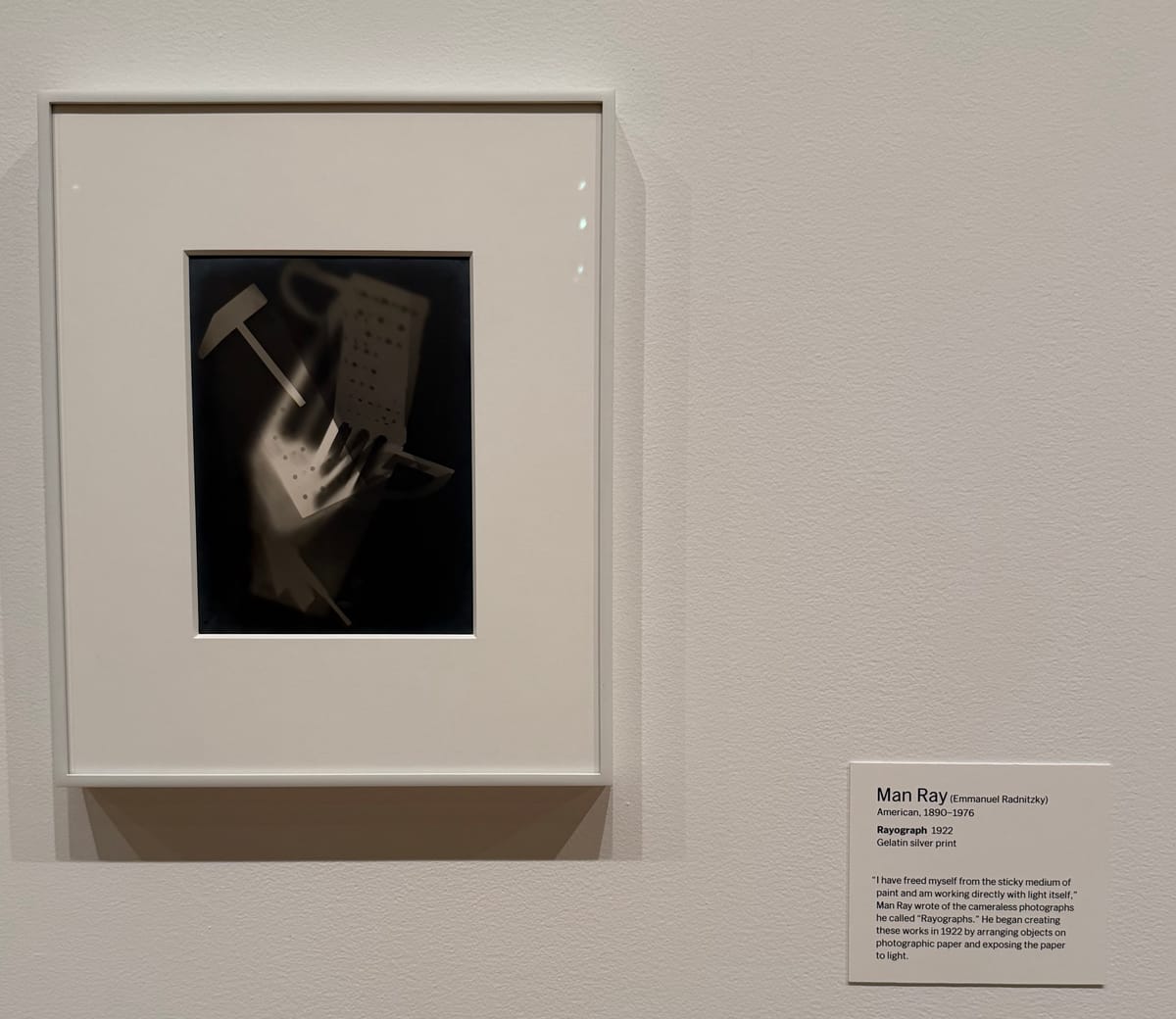

I stood in front of Man Ray's rayographs at the MoMA this fall, studying the ghostly white silhouettes floating against dark backgrounds. A glass funnel, a coil of wire, objects I couldn't quite identify. The wall text explained that he'd discovered the technique by accident in 1921, dropping unexposed photographic paper into a developing tray while working for a Parisian couturier. He placed random objects on the wet paper, turned on the light, and created images without a camera claiming "I have freed myself from the sticky medium of paint and am working directly with light itself."

What struck me wasn't the technique itself but the timeline. Photography had been invented eighty-two years earlier. For eight decades, photographers had been perfecting the craft of capturing reality through lenses. And then Man Ray discovered you didn't need a camera at all. The medium's most surreal, dreamlike capabilities emerged not at the beginning but after most people thought they understood what photography was.

I moved through the galleries. Monet's water lilies painted with portable tubes of paint that enabled working outdoors. Picasso's "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon" fracturing perspective two years after Einstein published his theory of relativity. Each work marked a moment when artists discovered what a technology could uniquely do, decades after everyone assumed they'd figured it out. And I kept thinking about AI.

We are roughly two years into understanding artificial intelligence as a creative tool. Which means we're approximately eighty years early.

The Pattern That Repeats

Every transformative creative technology follows the same arc. Invention comes first with clear intentions. The daguerreotype would create practical records. Portable paint tubes would solve storage problems. Then comes a long period of mimicry, where artists use the new tool to do what old tools already did. Early photography tried to look like painting. Early films recorded stage plays with stationary cameras.

Julia Margaret Cameron received her first camera in 1863 as a gift, with the note "It may amuse you." She wrote to a colleague: "I believe in other than mere conventional topographic photography, map-making and skeleton rendering of feature and form." But the Pictorialist movement she helped launch spent thirty years making photographs look like paintings with soft focus and hand-coloring.

The genuine discoveries came later. Man Ray described his process: "I deliberately dodged all the rules. I mixed the most insane products together, I used film way past its use-by date, I committed heinous crimes against chemistry and photography." His solarization technique, where the image partially reverses creating halo-like outlines, emerged in 1929 when a mouse ran over Lee Miller's foot in the darkroom, causing her to switch on the light mid-development. The mistake became the method.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir understood this about the humble paint tube: "Without colors in tubes, there would be no Cézanne, no Monet, no Pissarro, and no Impressionism." A simple storage solution enabled artists to work outdoors, capture changing light, embed sand from beaches directly into their paintings.

Lev Kuleshov discovered in the 1920s that audiences derived more meaning from two shots placed side-by-side than from single shots. The Kuleshov effect revolutionized cinema thirty years after its invention. Guitar distortion, initially an unwanted technical failure from damaged amplifiers, defined rock and blues decades after electric guitars were invented.

This pattern connects to a second historical truth. When technological or intellectual disruption overwhelms society, artists respond within years, not decades, creating conceptual frameworks when reality feels incomprehensible.

When Artists Process Crisis

Picasso completed "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon" in July 1907, just two years after Einstein published his theory of special relativity. Both men were responding to the same rupture. The realization that perspective, that space and time themselves, weren't absolute but depended on the observer's position. Picasso fractured his subjects into planes, showing multiple viewpoints simultaneously.

Technologies take decades to mature, but when they arrive during upheaval, artists create sense-making frameworks immediately. Cubism emerged two years after relativity. Dada launched eighteen months into World War I, when Hugo Ball performed nonsensical sound poems because rational language had produced mechanized slaughter. Marcel Duchamp submitted a signed urinal to an art show because if civilization could create the trenches, then civilization's definitions of art needed demolishing.

André Breton, who spent the war treating shell-shocked soldiers, founded Surrealism six years later with systematic methods for accessing "the superior reality of certain forms of previously neglected associations." Albert Camus wrote "The Myth of Sisyphus" in 1940 during the Fall of France, concluding: "The struggle itself towards the heights is enough to fill a man's heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy."

AI in 2025 sits at the intersection of both patterns. It's a technology whose creative potential will unfold over decades, but it's also arriving during a period of acceleration that demands immediate sense-making.

The Difference This Time

Current AI art mimics existing styles, generates competent work quickly. We're at the "photography imitating painting" stage. We're nowhere near discovering what AI uniquely enables.

But the timeline is compressed in ways history hasn't seen. Photography took sixty years to reach artistic maturity. AI tools moved from niche experimentation to widespread adoption in three years. Previous technologies emerged sequentially with decades between for adaptation. AI emerged simultaneously across text, image, music, video, and code. Every creative field disrupted at once.

This compression creates unique stress. The labor displacement is real. Illustrators, voice actors, background artists face obsolescence within a decade, before new roles emerge. The backlash follows historical patterns. Baudelaire warned photography would "supplant or corrupt" art. But this time the threatened livelihoods are immediate and widespread. Twenty thousand theater musicians lost work when sound came to film. That pattern repeats now, but faster.

AI also differs from historical precedents. Man Ray could manipulate darkroom chemistry. Guitarists could slash speaker cones with razor blades. The processes were comprehensible. AI operates as a black box, opaque even to its creators. Artists can't discover emergent properties by breaking the rules when they can't see the rules.

The corporate concentration matters too. Previous technologies eventually decentralized with many camera manufacturers, guitar builders, film formats. AI training requires massive computational resources concentrated in a handful of tech companies. OpenAI, Anthropic, Google control the foundational models, the training data, the algorithms. Artists need permission from tech platforms to experiment with the medium's core capabilities.

But open-weight models are emerging as a counterforce. Kimi K2 Thinking, a 1-trillion parameter model from Moonshot AI, was released as an open-weight model in November 2025. DeepSeek V3.2 offers performance rivaling Sonnet 4 at a fraction of the cost. Qwen3-Max is scored 74.8 on LiveCodeBench v6 coding benchmarks, competitive with closed models from far larger companies.

These open-weight releases change the power dynamic. An artist can now download and run substantial AI models locally, modify them, train them on specific datasets, explore their internal mechanisms. The decentralization that took decades with previous technologies might happen faster with AI precisely because developers recognize the danger of permanent corporate control.

The Transition From Mimicry to Discovery

Whether this decentralization enables genuine artistic experimentation remains the crucial question. But the transition from mimicry to discovery may already be starting.

Refik Anadol feeds thousands of architectural images into custom-trained models to create "Machine Hallucinations," massive projections that visualize latent space, the conceptual territory between images where the AI represents visual patterns. His 2022 installation at MoMA used 200 years of the museum's collection as training data. The work doesn't generate images in established styles. It visualizes how machine learning organizes visual knowledge itself.

Unsupervised - Machine Hallucinations, Refik Anadol

This parallels what Kuleshov discovered about montage or what Man Ray found in the darkroom. It reveals what the medium uniquely does. Anna Ridler trains models on her own hand-labeled datasets, photographing thousands of tulips. Helena Sarin creates abstract compositions by deliberately breaking GAN training processes, introducing glitches as aesthetic choices. These are the "heinous crimes against chemistry" of AI art.

But these remain early experiments. They're 1840s photography, not 1920s rayographs. The breakthrough applications will likely emerge from directions we haven't imagined.

Living in the Uncertainty

Three things seem clear from historical perspective.

First, the panic about AI killing art is misplaced. Photography freed painting to explore abstraction. Sound enabled new cinematic language. AI will force art to evolve, not eliminate it.

Second, concern about labor disruption is valid and urgent. This requires social intervention: safety nets, retraining programs, labor protections. The speed of change means we can't wait for natural adaptation.

Third, we're at year two of a thirty-to-seventy-year process. Current AI art is primitive relative to its eventual potential. We're in 1841, not 1921. The most interesting developments will surprise us.

Walking out into the November sun, I thought about Man Ray dropping that piece of photographic paper into the developer, watching ghostly shapes emerge. He couldn't have known he was discovering what photography uniquely could do. He was just playing, breaking rules, courting accidents.

We're at the beginning of that process with AI. The question is what artists will discover it can uniquely do, how corporate concentration versus open-source development will shape access to experimentation, and whether we can address labor displacement while discoveries unfold.

Man Ray needed eighty-two years after photography's invention to discover rayographs. We've been at this for two. The artists who define AI's creative potential are starting their work now. Some are training models on custom datasets in basement studios. Others are visualizing latent space in museums.

The work ahead requires both patience and urgency. Patience for the medium to reveal its nature, urgency to address the immediate human costs of transition. That tension is uncomfortable. It's also precisely what makes this moment both challenging and generative. The creative potential is genuinely unknown. That uncertainty is where the discoveries happen.